ORGANIZATIONAL REVITALIZATION: MAYA OR MOKSHA?(Excerpted)

{Excerpted and somewhat rephrased from an earlier publication as a chapter. The focus here is on organizations in India. It also holds implications for Indian/Hindu organizations outside of India.}

In the practice of management, organization development (revitalization of organizations) has come to be recognized as a systematic and planned approach to improving organizational competence and effectiveness. It seeks to align organizational results with its purposes, and overcome and/or avoid decay and senility.

While the techniques of Organization Development (OD) emerged in the USA in the 1950s, and are widely utilized in the developed countries of the west. They have been used to a much lesser extent, in the developing countries where the need for synergistic, healthy and productive organizations is more urgent and critical. Increasingly scholars and practitioners have called for OD to attune itself to be applicable around the globe (Brown 1988; Kiggundu, 1990; Srinivas, 1990).

This paper seeks to delineate the issue of the transferability of OD technology to developing countries for energizing their organizations. Specifically, this paper explores whether an indigenous approach to OD is feasible in the developing but ancient culture-nation of India. While some of its large organizations have lately developed into world class organizations, many continue to hold tremendous unrealized potential for improvements in productivity as well as in raising the quality of work life of their human resources (Kanungo and Misra, 1985; Mendonca and Kanungo, 1990). It has a unique cultural heritage that dates back to thousands of years, and it continues to have a significant impact on the day-to-day life of its population. Whether this cultural heritage supports organizational rot or revitalization and whether a unique and culture-sensitive approach to organizational renewal is possible are some of the questions posed in this paper.

APPLICATION OUTSIDE NORTH AMERICA

Broadly defined, OD includes almost any technique, policy or managerial practice used in a deliberate attempt to change individual behavior, organizational structure or technology for enhancing the accomplishment of the organization's objectives. Generally, in practice (and historically), only planned interventions for behavioral change are considered as OD. A significant attribute of OD is that it is a value based as opposed to a value neutral approach. The values (Golembiewski, 1991) including the methods used as well as the goals toward which OD interventions seek to move organizations are as follows:

1. It emphasizes and values openness, trust and collaborative effort.

2. It seeks simultaneously to meet the needs of individuals and of several levels of systems-small groups, large organizations, etc.

3. It is grounded in immediate experiences as they occur. This is reflected in the 'process analysis' of the personal and institutional forces acting on specific individuals and groups.

4. It emphasizes feelings and emotions, as well as ideas and concepts.

5. It attaches considerable importance to the individual's involvement and participation in an 'action research' sense-as subject, and object, as generator of data as well as responder to that.

6. It relies on group contexts for choice and change-to validate data, to develop and enforce norms, and to provide emotional support and identification.

7. It often begins with an emphasis on interaction, as creating norms for individual and group interaction, but may also include attempts to reinforce policies, procedures, and structures.

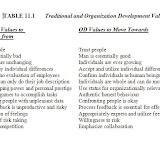

A description that predates the above by more than two decades (Tannenbaum and Davis, 1969), while not as comprehensive as the one above, supplies additional clarity by providing a contrast with the traditional values they seek to replace. This description is presented in Table 11.1 below. It suggests that where traditional values are strongly adhered to, and OD values are not subscribed to, organizational revitalization is most likely to be unsuccessful.

The following section explores whether the values prevailing in the Indian/Hindu culture are such that it is very unlikely that organizations would want to move towards vibrancy.

CREATING CULTURE SPECIFIC OD SYNERGY: A FOCUS ON INDIA

The Sanskrit word for culture is samskriti. The root sam means to synthesize. It is held that samskriti synthesizes or integrates the samskritas (those who possess samskriti) to the transcendental powers in the universe. In other words, samskriti is a current of human thought, sentiment and action which oversees superficial transactions and transitions (Panse, 1972). The thought follows a line of inquiry into the nature of one's own self and the self’s relation to the external world. Culture, according to Indian thought, is a function of people's cosmological concepts and philosophy of life, having to do with higher things in life, and with subtle things of the mind.

Perhaps a clearer conception of this notion of samskriti or culture is that of Sri Aurobindo (1971), a mystic and respected exponent of Indian philosophy and psychology. According to him, culture is the expression of a society's consciousness of life in terms of three aspects: (1) thoughts, ideals, upward will and aspirations; (2) creative self-expression of imagination and intelligence; and (3) outward and pragmatic formulation of the inspiring ideals under the practical constraints of time and space.

It may be noted that there are some western definitions of culture that are not too different. For example, Skinner (1964) suggested four aspects of culture: (a) assumptions and attitudes, (b) personal beliefs and aspirations, (c) interpersonal relationships, and (d) social structure. Assumptions and attitudes include how an individual views time, what will the future be, whether or not there is life after death, what an individual's duties and responsibilities are, and what he/she sees as his/her proper purpose in life. Personal beliefs and aspirations constitute an individual's views about right and wrong, sources of self-pride, fear and concern, hopes, and beliefs about the balance between a single person's importance vs. that of society's. Interpersonal relationships include the source of authority, whether or not an individual has empathy for others, the importance of the family to a person, where the objects of an individual's loyalty are located, and the extent of tolerance for personal differences. Social structure encompasses the amount of inter-class mobility, whether or not there is a class or caste system, whether the society is urban, farm or village, and what determines status in that culture.

Schein's (1981) definition is even closer to that of Sri Aurobindo. He has defined culture as consisting of three levels: (a) basic assumptions and premises, (b) values and ideology, and (c) artifacts and creations. The first level includes aspects like the relationship of man to man and man's concept of space and his place in it. These are usually taken for granted and are 'preconscious'. The middle level includes values and ideology, indicating ideals and goals as well as paths for achieving them. The third level includes language, technology and social organization. Each successive level is, to an extent, a manifestation of the one before it and thus all levels are interrelated.

It is interesting to note that both sage Aurobindo's and social scientist Schein's concepts of culture are in terms of levels, both having three levels. Furthermore, there is some similarity between Schein's second level, values and ideology, and Aurobindo's first level, religion and philosophy. They differ in terms of the importance they attach to this as the defining and predominant aspect of culture. According to Aurobindo's conception, religion and philosophy represent the most intense form of a people's upward will and aspiration and are the most emphatic disclosures of culture. The second aspect, the creative, imaginative and intellectual aspect refers to art, poetry, literature, dance, drama, music, architecture, etc. The third aspect, the outer and practical expression includes morals, mores, language, dress, food habits, and political-social organizations.

The indigenous Aurobindonian first level framework is adopted for the remainder of this paper for obvious reasons. To start off, the religious-philosophical ideals, upward will and aspirations of the primary Indian culture (also called Hindu, Sanatana or Vedanta) are presented in Table 11.3 below. Also noted in the table are contrasts from the western (Judeo-Christian) conceptions, which further helps to describe and distinguish the value framework in India for which appropriate OD interventions need to be envisioned. For, as noted earlier, the notions of OD evolved in the backdrop of the Judeo-Christian paradigm.

In order to derive implications from Table 11.3 for individual behavior in organizations it would help to take into account additional anchoring notions of Hinduism as described by a number of scholars (Ajaya, 1983; Brown, 1990; Das, 1989; Jacobs, 1961; Kenghe, 1972a, 1972b; Rama, Ballentine and Ajaya, 1976). The concepts of self, body, external world, and interpersonal relationships are unique in the Hindu orientation. It is held that the body is not the real person, but only an outer shell or clothing, and has a higher mission than just being a means of sensual experience. So an individual is enjoined to think that he has a body, but he is not the body; he has emotions, but he is not the emotions; that in his core, he is pure consciousness. The core is the inner spirit of the person, the-essential self. Death brings an end to the body, but not to its real core or atman. This inner self is accorded the highest importance as revealed by the following hymn. 'The spirit within me is smaller than a mustard seed; the spirit within me is greater than this earth and the sky and the heaven, and all these combined.'

The same atman is perceived to be at the core of all other lives and it is conceived that there is a fundamental and natural commonalty and equality amongst all human beings; there is no diversity, no real differences, all are the same, all are one. Ideal fife is a process of extending the self outward so that one is able to consider all others as equally dear, equally worthy, where one sees oneself in all others and regards all others the same as oneself. In other words, life is a process of becoming non-egotistical, equanimous and stable minded. Equanimity is the mental quality of accepting success and failure evenly without becoming elated by success or depressed and disappointed by failure. The important thing is to perform one's tasks and roles with a sense of service, dedication, joy, and without getting attached to expectations or be overly concerned with the outcomes.

Ideal life also places emphasis on non-violence and non-injury to others. An edict says, 'wound not others, nor injure by thought or deed; utter no word to pain thy fellow creatures.' The ideal fife is one of voluntary simplicity and a conservation minded enjoyment of wealth. Artha, kama, dharma and moksha are considered to be the major needs or life goals. Artha refers to basic economic necessities and worldly possessions. Kama refers to sensual pleasures and enjoyment of life. Dharma refers to ethical conduct in the pursuit of artha and kama. The fourth goal moksha refers to the universal desire for happiness, peace, and freedom or release from the limitations and difficulties of life. In addition it may be noted that there is also an ecological perspective – living with needs, eschewing wants, imbedded in the ideal life style.

Dharma is a complex concept. There is no single English word that is equivalent. Dharma means ethical conduct, law, duty, or path. Each person has to follow his or her dharma according to his/her essential nature. Following one's own dharma means 'being true to oneself'. The scriptures provide the injunction that it is better to do one's own dharma imperfectly than to do another's dharma, however well discharged -- ‘Better is death in one's own dharma, the dharma of another is fraught with liability.' One has to discern what one's nature is. Then, having acted according to one's dharma, one has to bear the consequences of one's actions. 'As one acts, as one conducts oneself, so does he/she become.' Thus, a person is regarded as the creator of his own fate. He cannot escape from the effects of his prior deeds; but he can influence his future by his thoughts and deeds in the present.

Pious life (religious living) may be pursued according to one of the four life anchors – jnana, or the path of analytical intellectuality; bhakti or the path of image worship and devotion; karma, or path of selfless service to others; and yoga, the disciplined and step-wise path of which there are many. Individuals are free to pursue any one or any combination of these. Pursuing a chosen life anchor is the way to break out of maya which is a veil of darkness or ignorance which makes one concentrate on mere form rather than substance, on illusions rather than reality.

In the light of the above description of the Indian psycho-philosophy, we can now ask what the implications are of the Vedantic values and world view (Table 11.3 below) for organizational change and OD. Devoid of the religious connotations and objectives they seem to suggest the following: persons are not too different from each other; social distances and differences are only apparent and superficial; there is a fundamental equality amongst all people; perception of differences is due to ignorance; one reaps what one sows because of the cause-effect chain; one has the key to open the door to one's own future; change is inevitable and inherently positive; growth takes place by going inward and seeking to better oneself as a person; ethical and moral conduct is not only desirable but necessary; ignorance, not evil intentions, is the cause of erroneous behavior; the 'present' or 'here and now' is as important a determinant of the future as the past has been a determinant of the present; enhancing one's own growth and development is both acceptable and desirable; emotion laden as well as intellectual-analytical methods are acceptable and valid in the pursuit of one's growth and development.

What do these mean for organizational change and change agents? The notions of inquiry, investigation, introspective self-examination, and pursuit of personal growth towards perfection are fundamental to the Indian Vedanta framework. Learning, growth, and change are acceptable. Since the core beliefs in their details are complex and may even be contradictory, and especially because the principle of equifinality appears to be an integral part of the belief system, it may be difficult for change agents to suggest a particular technique or method as the appropriate one in a given situation. Because of the beliefs that time is endless and cyclical and that growth and change occur over an extended period of time, it may also be difficult to convince that timely action is necessary and important.

Although the way of life advocated by religion is still aspired to by a vast majority of Indians, in actual practice, however, there is a lag effect. For a great majority, the social self's extension outward is limited, going no farther than the in-group (extended family, caste group, etc.). The out-groups consist of others toward whom one tends to be indifferent, irresponsible, or even exploitative. This lag between what is valued and what is practiced may in part be due to the 'present times' scarcities of the basic necessities of life that focus attention on short-term survival realities. Partly, it may also be a residual mental set of inferiority, uncertainty and anxiety resulting from centuries of external domination first by Muslim invaders and then by European colonial rulers. On the positive side, there is emotional support from the in-group, both in times of happiness and misery. There is affection and care of subordinates who reciprocate with respectful compliance. Relationships are not temporary or merely contractual. Contacts, connections, and attachments are very important. People are not only means but are also supportive anchors during times of emotional distress (Verma, 1987). It is indeed remarkable that the ancient value system still holds sway over a population that has not experienced much long term social stability.

Table 11.3 here

Thus, the values stemming from the religio-philosophical origins appear to be sufficiently facilitative of OD interventions. Nurturing feminine values, concern for maintenance behavior, importance of doing one's best, reality recognition, and stress preparedness (in the sense of accepting that results may be influenced by extraneous conditions) are all supportive of change and growth. However, confrontation in a face-to-face situation is not valued. But the expression of emotionality appears to be acceptable. Emotional release may be orchestrated in a non-confrontational way through the process of self-examination for growth and development which the value system seems to permit. Confrontations connote public defrocking with accompanying embarrassment, loss of face, and dignity.

The in-group vs. out-group feelings may be more of a problem. The strong group loyalty has a potential for groupthink errors in decision-making. Some of the other factors include individuals willing to forego task relevant behaviors so as to maintain a relationship. The focus on maintaining relationships also leads to a certain degree of hypocrisy, an unwillingness to make one's stand clear on any issue, because of the risk of alienating relationships. The self thrives on the care and concern shown by the in-group, and is almost ineffective in handling demanding situations independently. Such a social self may undermine autonomy, initiative, and individualism. Often, excessive expectations are placed on those in the subordinate role. Asking and giving are highly emotional and one is likely to feel disappointed and hurt if ignored. In addition, inequality, injustice, exploitation, and cruelty are usually expressed toward members of the out-group (Verma, 1987).

Kanungo (1990) has noted that workplace commitment may be because of the paramount importance attached to family well-being, work is important only for making and maintaining people connections. Altruism may lead to inappropriate sacrifice of self interest to the benefit of incompetents. Equanimity may be erroneously equated with acceptance of undesirable statusquo or unconcerned mechanical behavior. Such misunderstanding or misreading of cultural norms and messages is possible under certain conditions. To an extent such misunderstanding may also be a reaction and defense towards prevailing workplace conditions.

OD practitioners need to work around such defenses and educate and interpret cultural injunctions, scriptural passages, mythology, and religious injunctions. Thus, a change agent in India cannot afford to be ignorant of its psycho-philosophy, religion and mythology. If consequences are clearly spelled out to the people, if analogous situations from the cultural background are juxtaposed, realistic, constructive and creative behavior is likely to follow. The religious-philosophical injunctions repeatedly emphasize adherence to truth and right conduct. 'Satyam vadishyami, dharmam karishyami' means 'I will pursue truth, I will act according to dharma.' Such injunctions can be drawn upon as reasons for introducing change and attempts to improve the quality of work life for all concerned.

The next section that goes on to explore and examine whether the Hindu/Indian culture is conducive to organizational development and revitalization is posted separately with its section heading AN INDIAN PARADIGM FOR INTRODUCING CHANGE. It introduces and elaborates the age old mode of ekottaropaya (in English, the technique of just-one-more).

But for now, from what has been said above the question I would like to pose my compatriots is whether Hindu/Indian organizations – whether profit or non-profit, whether religious or secular, whether in India or outside India – have appropriate mindsets that are conducive to organizational and personal growth and change or betterment. I would appreciate if you will use the comments section below to pen your thoughts and share with others. Here is how you can do so:

Just below this posting there is a under lined word ‘comments’ Click that word, and the box for your comments opens. If there are any comments already, then the box for your comments will be at the bottom of them all. You pen your thoughts in the box. At the bottom of that comment box is a small box with an arrow next to it. Click the arrow, for your choice of whether you want your email address to appear under your comments, or just anonymous. Then clique DONE.

Excerpted and somewhat rephrased from Kalburgi M. Srinivas. Organization Development: Maya or Moksha. Pp 248- 282, Chapter 11 in Work Motivation: Models for Developing Countries, Edited by R.N.Kanungo and M. Mendonca, Sage Publications, 1994. If interested you may read the original chapter that first talks about developing countries and contexts prior to the above section on India.

In the practice of management, organization development (revitalization of organizations) has come to be recognized as a systematic and planned approach to improving organizational competence and effectiveness. It seeks to align organizational results with its purposes, and overcome and/or avoid decay and senility.

While the techniques of Organization Development (OD) emerged in the USA in the 1950s, and are widely utilized in the developed countries of the west. They have been used to a much lesser extent, in the developing countries where the need for synergistic, healthy and productive organizations is more urgent and critical. Increasingly scholars and practitioners have called for OD to attune itself to be applicable around the globe (Brown 1988; Kiggundu, 1990; Srinivas, 1990).

This paper seeks to delineate the issue of the transferability of OD technology to developing countries for energizing their organizations. Specifically, this paper explores whether an indigenous approach to OD is feasible in the developing but ancient culture-nation of India. While some of its large organizations have lately developed into world class organizations, many continue to hold tremendous unrealized potential for improvements in productivity as well as in raising the quality of work life of their human resources (Kanungo and Misra, 1985; Mendonca and Kanungo, 1990). It has a unique cultural heritage that dates back to thousands of years, and it continues to have a significant impact on the day-to-day life of its population. Whether this cultural heritage supports organizational rot or revitalization and whether a unique and culture-sensitive approach to organizational renewal is possible are some of the questions posed in this paper.

APPLICATION OUTSIDE NORTH AMERICA

Broadly defined, OD includes almost any technique, policy or managerial practice used in a deliberate attempt to change individual behavior, organizational structure or technology for enhancing the accomplishment of the organization's objectives. Generally, in practice (and historically), only planned interventions for behavioral change are considered as OD. A significant attribute of OD is that it is a value based as opposed to a value neutral approach. The values (Golembiewski, 1991) including the methods used as well as the goals toward which OD interventions seek to move organizations are as follows:

1. It emphasizes and values openness, trust and collaborative effort.

2. It seeks simultaneously to meet the needs of individuals and of several levels of systems-small groups, large organizations, etc.

3. It is grounded in immediate experiences as they occur. This is reflected in the 'process analysis' of the personal and institutional forces acting on specific individuals and groups.

4. It emphasizes feelings and emotions, as well as ideas and concepts.

5. It attaches considerable importance to the individual's involvement and participation in an 'action research' sense-as subject, and object, as generator of data as well as responder to that.

6. It relies on group contexts for choice and change-to validate data, to develop and enforce norms, and to provide emotional support and identification.

7. It often begins with an emphasis on interaction, as creating norms for individual and group interaction, but may also include attempts to reinforce policies, procedures, and structures.

A description that predates the above by more than two decades (Tannenbaum and Davis, 1969), while not as comprehensive as the one above, supplies additional clarity by providing a contrast with the traditional values they seek to replace. This description is presented in Table 11.1 below. It suggests that where traditional values are strongly adhered to, and OD values are not subscribed to, organizational revitalization is most likely to be unsuccessful.

|

| Tables 11 |

The following section explores whether the values prevailing in the Indian/Hindu culture are such that it is very unlikely that organizations would want to move towards vibrancy.

CREATING CULTURE SPECIFIC OD SYNERGY: A FOCUS ON INDIA

The Sanskrit word for culture is samskriti. The root sam means to synthesize. It is held that samskriti synthesizes or integrates the samskritas (those who possess samskriti) to the transcendental powers in the universe. In other words, samskriti is a current of human thought, sentiment and action which oversees superficial transactions and transitions (Panse, 1972). The thought follows a line of inquiry into the nature of one's own self and the self’s relation to the external world. Culture, according to Indian thought, is a function of people's cosmological concepts and philosophy of life, having to do with higher things in life, and with subtle things of the mind.

Perhaps a clearer conception of this notion of samskriti or culture is that of Sri Aurobindo (1971), a mystic and respected exponent of Indian philosophy and psychology. According to him, culture is the expression of a society's consciousness of life in terms of three aspects: (1) thoughts, ideals, upward will and aspirations; (2) creative self-expression of imagination and intelligence; and (3) outward and pragmatic formulation of the inspiring ideals under the practical constraints of time and space.

It may be noted that there are some western definitions of culture that are not too different. For example, Skinner (1964) suggested four aspects of culture: (a) assumptions and attitudes, (b) personal beliefs and aspirations, (c) interpersonal relationships, and (d) social structure. Assumptions and attitudes include how an individual views time, what will the future be, whether or not there is life after death, what an individual's duties and responsibilities are, and what he/she sees as his/her proper purpose in life. Personal beliefs and aspirations constitute an individual's views about right and wrong, sources of self-pride, fear and concern, hopes, and beliefs about the balance between a single person's importance vs. that of society's. Interpersonal relationships include the source of authority, whether or not an individual has empathy for others, the importance of the family to a person, where the objects of an individual's loyalty are located, and the extent of tolerance for personal differences. Social structure encompasses the amount of inter-class mobility, whether or not there is a class or caste system, whether the society is urban, farm or village, and what determines status in that culture.

Schein's (1981) definition is even closer to that of Sri Aurobindo. He has defined culture as consisting of three levels: (a) basic assumptions and premises, (b) values and ideology, and (c) artifacts and creations. The first level includes aspects like the relationship of man to man and man's concept of space and his place in it. These are usually taken for granted and are 'preconscious'. The middle level includes values and ideology, indicating ideals and goals as well as paths for achieving them. The third level includes language, technology and social organization. Each successive level is, to an extent, a manifestation of the one before it and thus all levels are interrelated.

It is interesting to note that both sage Aurobindo's and social scientist Schein's concepts of culture are in terms of levels, both having three levels. Furthermore, there is some similarity between Schein's second level, values and ideology, and Aurobindo's first level, religion and philosophy. They differ in terms of the importance they attach to this as the defining and predominant aspect of culture. According to Aurobindo's conception, religion and philosophy represent the most intense form of a people's upward will and aspiration and are the most emphatic disclosures of culture. The second aspect, the creative, imaginative and intellectual aspect refers to art, poetry, literature, dance, drama, music, architecture, etc. The third aspect, the outer and practical expression includes morals, mores, language, dress, food habits, and political-social organizations.

The indigenous Aurobindonian first level framework is adopted for the remainder of this paper for obvious reasons. To start off, the religious-philosophical ideals, upward will and aspirations of the primary Indian culture (also called Hindu, Sanatana or Vedanta) are presented in Table 11.3 below. Also noted in the table are contrasts from the western (Judeo-Christian) conceptions, which further helps to describe and distinguish the value framework in India for which appropriate OD interventions need to be envisioned. For, as noted earlier, the notions of OD evolved in the backdrop of the Judeo-Christian paradigm.

|

| From Tables 11 |

|

| From Tables 11 |

In order to derive implications from Table 11.3 for individual behavior in organizations it would help to take into account additional anchoring notions of Hinduism as described by a number of scholars (Ajaya, 1983; Brown, 1990; Das, 1989; Jacobs, 1961; Kenghe, 1972a, 1972b; Rama, Ballentine and Ajaya, 1976). The concepts of self, body, external world, and interpersonal relationships are unique in the Hindu orientation. It is held that the body is not the real person, but only an outer shell or clothing, and has a higher mission than just being a means of sensual experience. So an individual is enjoined to think that he has a body, but he is not the body; he has emotions, but he is not the emotions; that in his core, he is pure consciousness. The core is the inner spirit of the person, the-essential self. Death brings an end to the body, but not to its real core or atman. This inner self is accorded the highest importance as revealed by the following hymn. 'The spirit within me is smaller than a mustard seed; the spirit within me is greater than this earth and the sky and the heaven, and all these combined.'

The same atman is perceived to be at the core of all other lives and it is conceived that there is a fundamental and natural commonalty and equality amongst all human beings; there is no diversity, no real differences, all are the same, all are one. Ideal fife is a process of extending the self outward so that one is able to consider all others as equally dear, equally worthy, where one sees oneself in all others and regards all others the same as oneself. In other words, life is a process of becoming non-egotistical, equanimous and stable minded. Equanimity is the mental quality of accepting success and failure evenly without becoming elated by success or depressed and disappointed by failure. The important thing is to perform one's tasks and roles with a sense of service, dedication, joy, and without getting attached to expectations or be overly concerned with the outcomes.

Ideal life also places emphasis on non-violence and non-injury to others. An edict says, 'wound not others, nor injure by thought or deed; utter no word to pain thy fellow creatures.' The ideal fife is one of voluntary simplicity and a conservation minded enjoyment of wealth. Artha, kama, dharma and moksha are considered to be the major needs or life goals. Artha refers to basic economic necessities and worldly possessions. Kama refers to sensual pleasures and enjoyment of life. Dharma refers to ethical conduct in the pursuit of artha and kama. The fourth goal moksha refers to the universal desire for happiness, peace, and freedom or release from the limitations and difficulties of life. In addition it may be noted that there is also an ecological perspective – living with needs, eschewing wants, imbedded in the ideal life style.

Dharma is a complex concept. There is no single English word that is equivalent. Dharma means ethical conduct, law, duty, or path. Each person has to follow his or her dharma according to his/her essential nature. Following one's own dharma means 'being true to oneself'. The scriptures provide the injunction that it is better to do one's own dharma imperfectly than to do another's dharma, however well discharged -- ‘Better is death in one's own dharma, the dharma of another is fraught with liability.' One has to discern what one's nature is. Then, having acted according to one's dharma, one has to bear the consequences of one's actions. 'As one acts, as one conducts oneself, so does he/she become.' Thus, a person is regarded as the creator of his own fate. He cannot escape from the effects of his prior deeds; but he can influence his future by his thoughts and deeds in the present.

Pious life (religious living) may be pursued according to one of the four life anchors – jnana, or the path of analytical intellectuality; bhakti or the path of image worship and devotion; karma, or path of selfless service to others; and yoga, the disciplined and step-wise path of which there are many. Individuals are free to pursue any one or any combination of these. Pursuing a chosen life anchor is the way to break out of maya which is a veil of darkness or ignorance which makes one concentrate on mere form rather than substance, on illusions rather than reality.

In the light of the above description of the Indian psycho-philosophy, we can now ask what the implications are of the Vedantic values and world view (Table 11.3 below) for organizational change and OD. Devoid of the religious connotations and objectives they seem to suggest the following: persons are not too different from each other; social distances and differences are only apparent and superficial; there is a fundamental equality amongst all people; perception of differences is due to ignorance; one reaps what one sows because of the cause-effect chain; one has the key to open the door to one's own future; change is inevitable and inherently positive; growth takes place by going inward and seeking to better oneself as a person; ethical and moral conduct is not only desirable but necessary; ignorance, not evil intentions, is the cause of erroneous behavior; the 'present' or 'here and now' is as important a determinant of the future as the past has been a determinant of the present; enhancing one's own growth and development is both acceptable and desirable; emotion laden as well as intellectual-analytical methods are acceptable and valid in the pursuit of one's growth and development.

What do these mean for organizational change and change agents? The notions of inquiry, investigation, introspective self-examination, and pursuit of personal growth towards perfection are fundamental to the Indian Vedanta framework. Learning, growth, and change are acceptable. Since the core beliefs in their details are complex and may even be contradictory, and especially because the principle of equifinality appears to be an integral part of the belief system, it may be difficult for change agents to suggest a particular technique or method as the appropriate one in a given situation. Because of the beliefs that time is endless and cyclical and that growth and change occur over an extended period of time, it may also be difficult to convince that timely action is necessary and important.

Although the way of life advocated by religion is still aspired to by a vast majority of Indians, in actual practice, however, there is a lag effect. For a great majority, the social self's extension outward is limited, going no farther than the in-group (extended family, caste group, etc.). The out-groups consist of others toward whom one tends to be indifferent, irresponsible, or even exploitative. This lag between what is valued and what is practiced may in part be due to the 'present times' scarcities of the basic necessities of life that focus attention on short-term survival realities. Partly, it may also be a residual mental set of inferiority, uncertainty and anxiety resulting from centuries of external domination first by Muslim invaders and then by European colonial rulers. On the positive side, there is emotional support from the in-group, both in times of happiness and misery. There is affection and care of subordinates who reciprocate with respectful compliance. Relationships are not temporary or merely contractual. Contacts, connections, and attachments are very important. People are not only means but are also supportive anchors during times of emotional distress (Verma, 1987). It is indeed remarkable that the ancient value system still holds sway over a population that has not experienced much long term social stability.

Table 11.3 here

Thus, the values stemming from the religio-philosophical origins appear to be sufficiently facilitative of OD interventions. Nurturing feminine values, concern for maintenance behavior, importance of doing one's best, reality recognition, and stress preparedness (in the sense of accepting that results may be influenced by extraneous conditions) are all supportive of change and growth. However, confrontation in a face-to-face situation is not valued. But the expression of emotionality appears to be acceptable. Emotional release may be orchestrated in a non-confrontational way through the process of self-examination for growth and development which the value system seems to permit. Confrontations connote public defrocking with accompanying embarrassment, loss of face, and dignity.

The in-group vs. out-group feelings may be more of a problem. The strong group loyalty has a potential for groupthink errors in decision-making. Some of the other factors include individuals willing to forego task relevant behaviors so as to maintain a relationship. The focus on maintaining relationships also leads to a certain degree of hypocrisy, an unwillingness to make one's stand clear on any issue, because of the risk of alienating relationships. The self thrives on the care and concern shown by the in-group, and is almost ineffective in handling demanding situations independently. Such a social self may undermine autonomy, initiative, and individualism. Often, excessive expectations are placed on those in the subordinate role. Asking and giving are highly emotional and one is likely to feel disappointed and hurt if ignored. In addition, inequality, injustice, exploitation, and cruelty are usually expressed toward members of the out-group (Verma, 1987).

Kanungo (1990) has noted that workplace commitment may be because of the paramount importance attached to family well-being, work is important only for making and maintaining people connections. Altruism may lead to inappropriate sacrifice of self interest to the benefit of incompetents. Equanimity may be erroneously equated with acceptance of undesirable statusquo or unconcerned mechanical behavior. Such misunderstanding or misreading of cultural norms and messages is possible under certain conditions. To an extent such misunderstanding may also be a reaction and defense towards prevailing workplace conditions.

OD practitioners need to work around such defenses and educate and interpret cultural injunctions, scriptural passages, mythology, and religious injunctions. Thus, a change agent in India cannot afford to be ignorant of its psycho-philosophy, religion and mythology. If consequences are clearly spelled out to the people, if analogous situations from the cultural background are juxtaposed, realistic, constructive and creative behavior is likely to follow. The religious-philosophical injunctions repeatedly emphasize adherence to truth and right conduct. 'Satyam vadishyami, dharmam karishyami' means 'I will pursue truth, I will act according to dharma.' Such injunctions can be drawn upon as reasons for introducing change and attempts to improve the quality of work life for all concerned.

The next section that goes on to explore and examine whether the Hindu/Indian culture is conducive to organizational development and revitalization is posted separately with its section heading AN INDIAN PARADIGM FOR INTRODUCING CHANGE. It introduces and elaborates the age old mode of ekottaropaya (in English, the technique of just-one-more).

But for now, from what has been said above the question I would like to pose my compatriots is whether Hindu/Indian organizations – whether profit or non-profit, whether religious or secular, whether in India or outside India – have appropriate mindsets that are conducive to organizational and personal growth and change or betterment. I would appreciate if you will use the comments section below to pen your thoughts and share with others. Here is how you can do so:

Just below this posting there is a under lined word ‘comments’ Click that word, and the box for your comments opens. If there are any comments already, then the box for your comments will be at the bottom of them all. You pen your thoughts in the box. At the bottom of that comment box is a small box with an arrow next to it. Click the arrow, for your choice of whether you want your email address to appear under your comments, or just anonymous. Then clique DONE.

Excerpted and somewhat rephrased from Kalburgi M. Srinivas. Organization Development: Maya or Moksha. Pp 248- 282, Chapter 11 in Work Motivation: Models for Developing Countries, Edited by R.N.Kanungo and M. Mendonca, Sage Publications, 1994. If interested you may read the original chapter that first talks about developing countries and contexts prior to the above section on India.

Labels: Hindu organizations, India, Organization renewal

2 Comments:

Terrific post and to the point. I am not sure if this describes the truth is the best place to inquire

about nevertheless does one folk have just about any what it really where you get a few ghost

writers? Thank you beforehand.

My webpage ; http://aboutme0012.blogspot.com/

By Anonymous, At

December 10, 2012 at 7:54 PM

Anonymous, At

December 10, 2012 at 7:54 PM

Terrific posting, I think don’t imagination only take advantage of this post as

part of my own e book review.

My blog : Treating Genital Warts

By Anonymous, At

December 11, 2012 at 2:20 AM

Anonymous, At

December 11, 2012 at 2:20 AM

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home